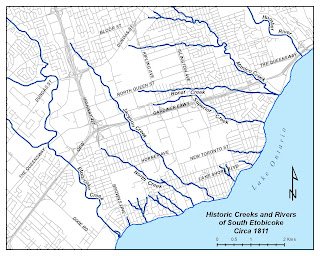

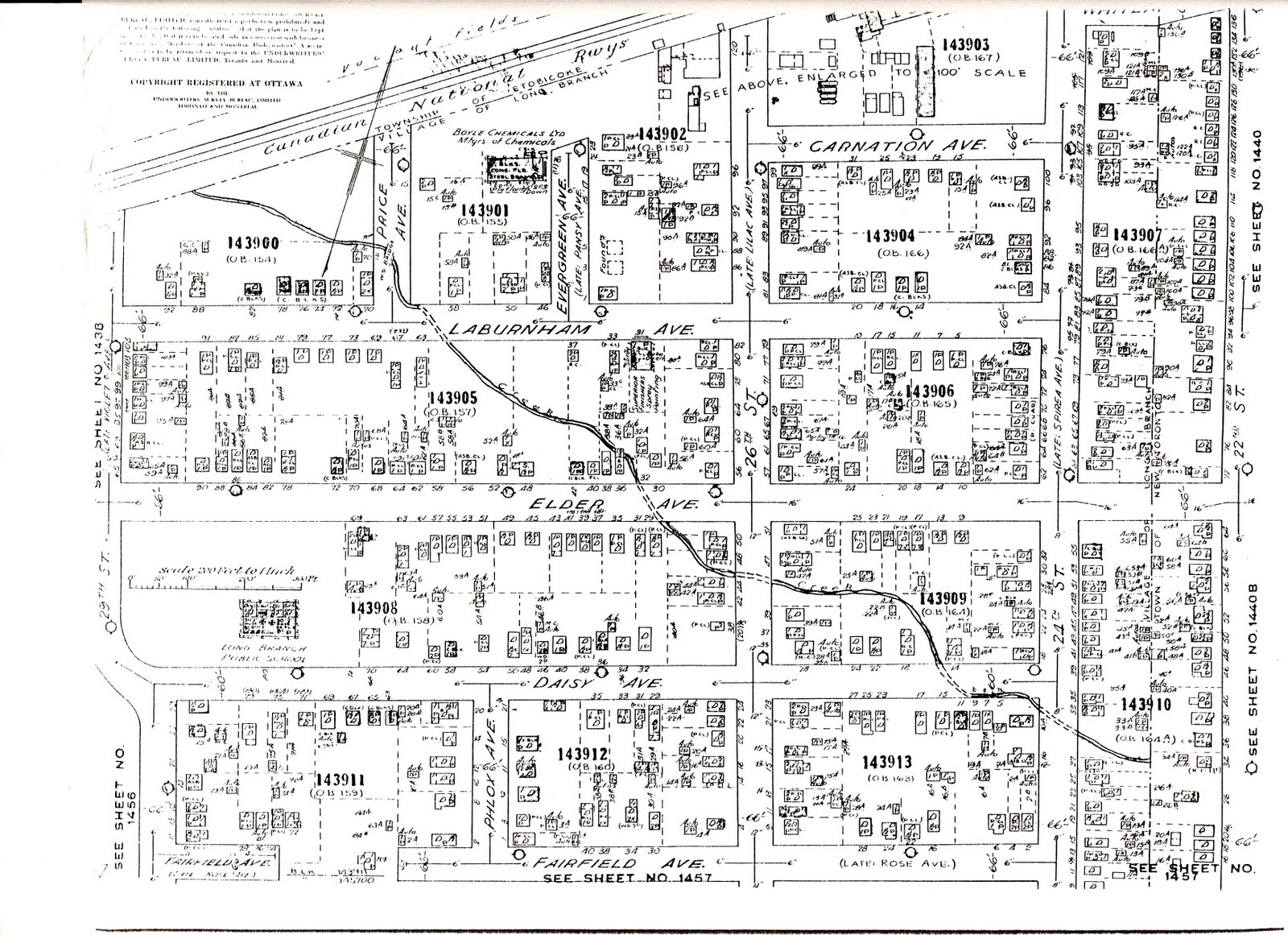

The Creeks of 1811

The lost creeks of South Etobicoke as they existed in 1811, superimposed over today's street grid. Map courtesy of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority.

The history and restoration of the buried waterways that once flowed through what is now southwest Toronto

The lost creeks of South Etobicoke as they existed in 1811, superimposed over today's street grid. Map courtesy of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority.

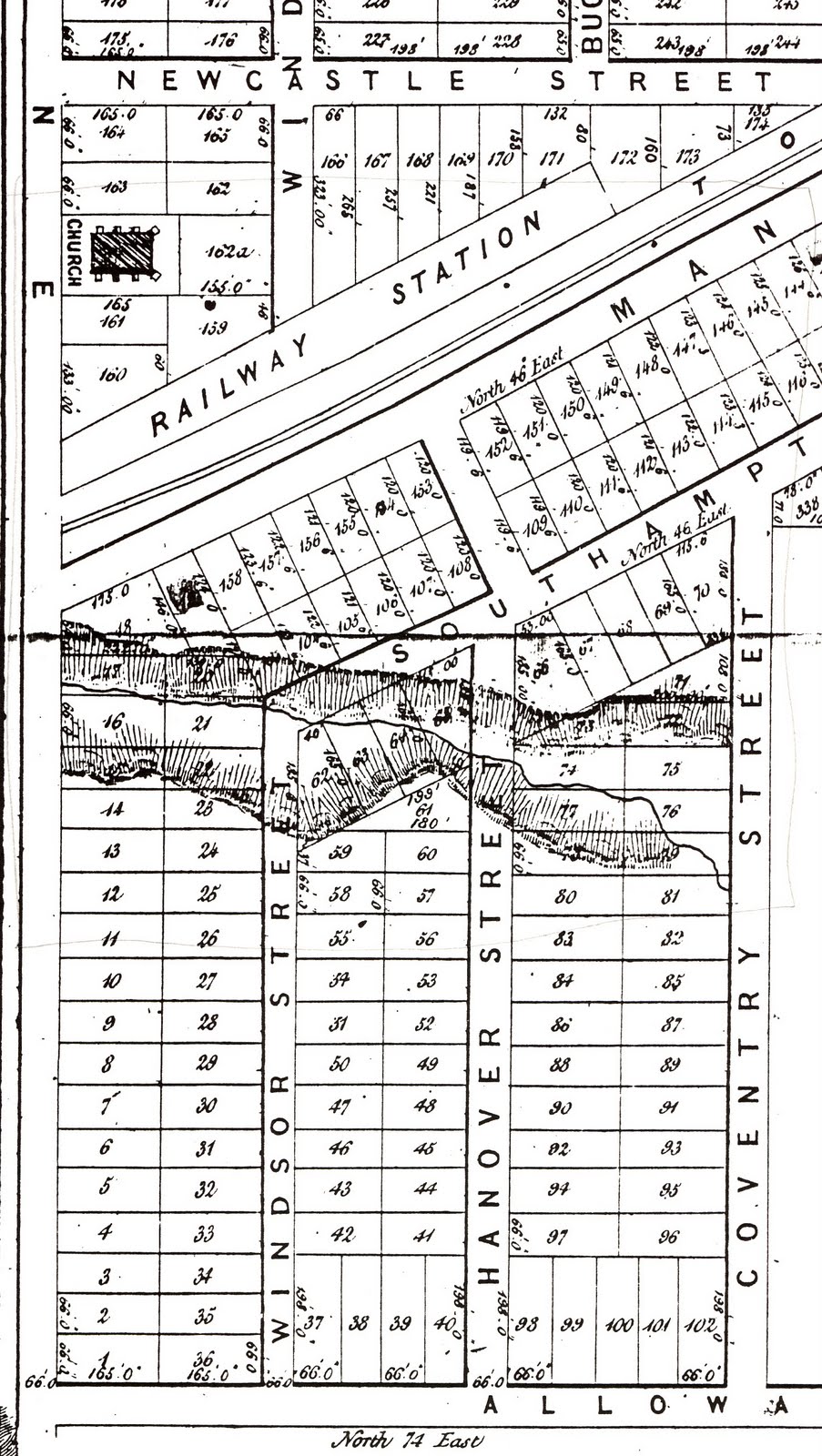

The 1811 patent map reveals a landscape vastly different from today—one laced with creeks and streams flowing from the heights of land toward Lake Ontario. North Creek, Jackson Creek, Superior Creek, and Bonar Creek once carved their paths through thick forests, providing habitat for salmon and sustaining the Mississauga people who had lived here for thousands of years.

While most creeks in the old City of Toronto were buried in sewer lines long ago, many of the original creeks of South Etobicoke survived into the mid-20th century—and some significant portions still exist today. Their survival was a matter of geography and timing: located west of York, the area developed more slowly, giving these waterways a longer life.

"However you can still catch glimpses of many of these creeks and streams if you know where to look."

The lands surrounding Toronto, including all of Etobicoke, were acquired from the resident Ojibwa Mississauga nation as part of the Toronto Purchase in 1787. The treaty established the rights of the Mississauga to continue cultivating the lands at the mouth of Etobicoke Creek.

It was the Mississauga nation who gave place names to many South Etobicoke locations, names that speak to the ecological richness of the landscape before European settlement.

"Home of the wild pigeon"

"Where the alders grow"

"Small streams and creeks"

Jackson Creek once drained a large area of south Etobicoke, originating just north of Bloor Street West near Highway 427 and flowing in a southeasterly direction to Lake Ontario. Miraculously it still flows through most of its upper reaches north of the Gardiner Expressway.

Had the area been developed as a residential community, the creek would most likely have been buried. Instead, it was shunted off to the sides of large industrial and commercial properties, and though channelized, is now largely vegetated by trees and bullrushes.

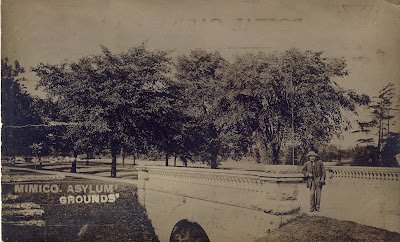

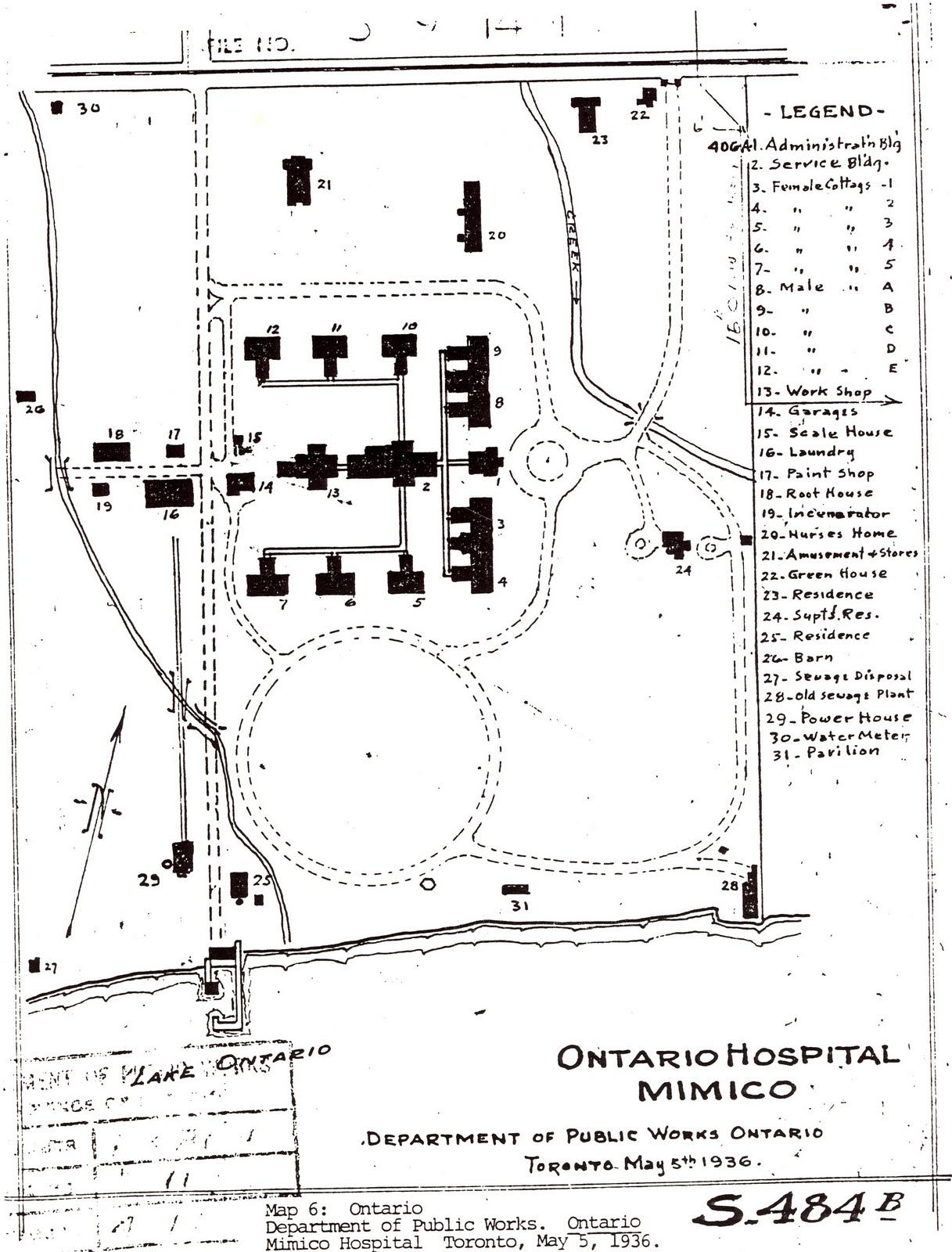

"On the Hospital Grounds its former valley can still be seen. Today it is called 'the swale'. Underneath, Jackson Creek flows through a storm sewer along its former course."

When the entrance to the Hospital was developed in the late 19th century, an ornate stone bridge was built across the creek. The balustrade has been removed but the historic bridge remains buried under fill, waiting to be resurrected.

North Creek originally drained a large area of south Etobicoke, flowing in a southeasterly direction to Lake Ontario from its headwaters near the interchange of present day Gardiner Expressway and Highway 427.

Most of the creek was placed in a sewer sometime after 1958, following four years of complaints that industry was dumping waste in the creek. At a Long Branch Council meeting in 1954, Councillor Maurice Breen openly admitted this was a problem, but explained the local sewage plant was already overloaded.

Today it disappears into a sewer just south of Laburnham Park, popping up on the Hospital Grounds at the foot of Kipling Avenue. Even though it has now been hijacked as a storm water system, the flow is relatively constant, providing important habitat for migrant warblers, black-crowned night herons, foxes and beavers.

"Originally covered by thick forests, these watersheds evolved over thousands of years to become a finely tuned and balanced system that produced a steady flow of cool, clear and pristine water abounding in sensitive coldwater fish species such as salmon."— Michael Harrison, Lost Creeks of South Etobicoke

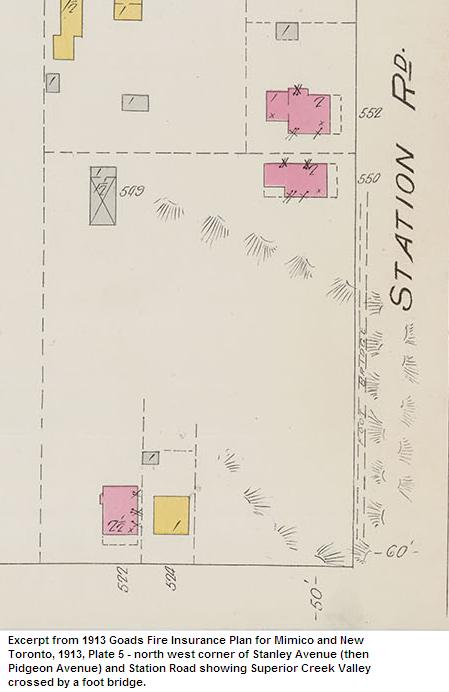

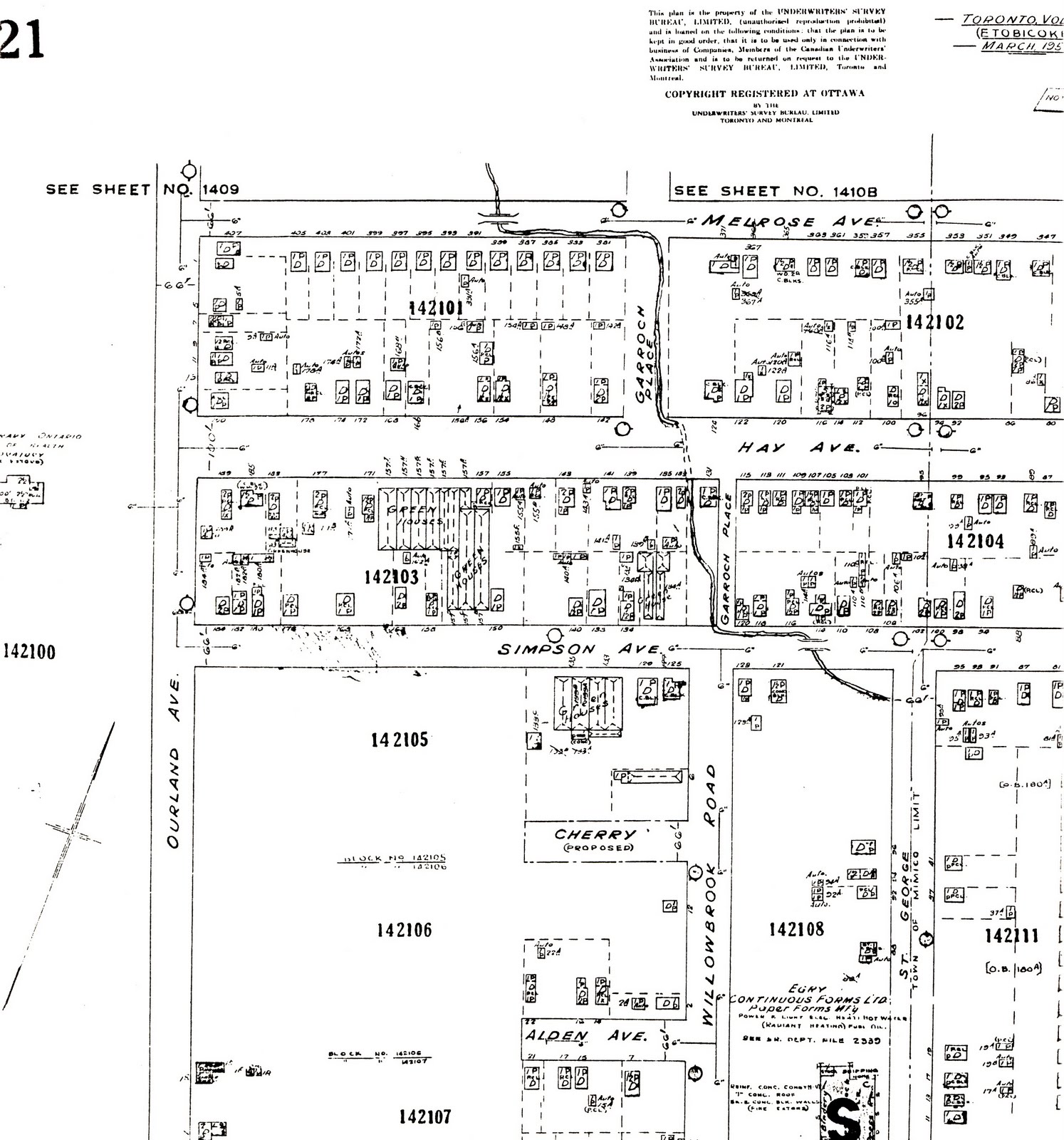

The headwaters of Superior Creek originated near present day Kipling Avenue, just north of the Gardiner Expressway, and flowed in a southeasterly direction to Lake Ontario through what is now Mimico.

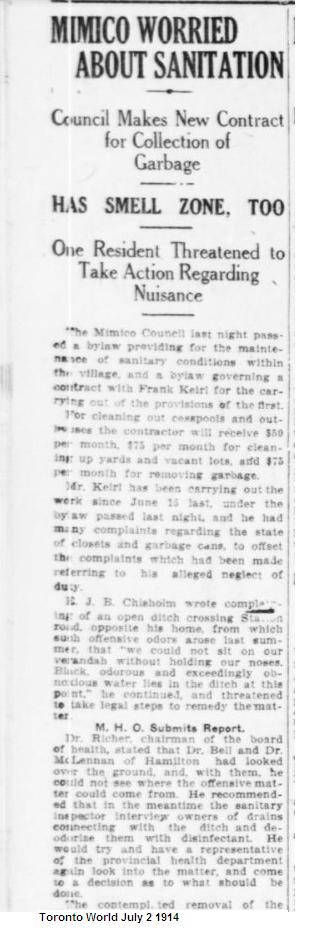

Complaints regarding pollution in the creek from local industry and the nearby railway led to the lower portion being modified and piped in 1915 by the Town of Mimico as an infrastructure project to alleviate local unemployment.

The upper portion continued to flow freely across north Mimico until construction of new homes after WWII led to citizen complaints over pollution and safety. Articles began appearing in the Advertiser in the early 1950s when residents demanded action. One resident even threatened a tax boycott until the creek was gone.

"Today, nothing remains of the creek, and a river of black asphalt covers the lower portion where it once flowed in a wide and steep ravine down Stanley Avenue."

Bonar Creek, a tributary of Mimico Creek, had its headwaters just north of Superior Creek and flowed in a southeasterly direction until it joined up with Mimico Creek at its vast wetland at Lake Ontario.

It continued to flow until about 1950, when most of it was placed in a sewer and parts of its former watercourse was filled in and topped with warehouses and a sewage treatment plant. In 1957, the operators of the McGuiness Distillery began to fill in the remainder of the creek's ravine to construct warehouses.

Today only the lower portion of the creek below the CNR rail line flows above ground, though it has been channelized.

However, restoration of the creek is in process. The Bonar Creek Stormwater Management Facility will result in the restoration of the wetland that historically existed in this location.

Lands acquired from the Ojibwa Mississauga nation, who had lived here for over 11,000 years.

Sawmill established on the Humber River in Etobicoke. Superior wood in this location was highly sought after for construction of early York.

Forest depletion reaches 50%. Severe floods begin destroying mills as the water table drops and runoff increases.

Not enough water in Etobicoke Creek to turn the great wheel at the Dundas Road mill. Water fluctuations devastate salmon populations.

Superior Creek's lower portion piped by the Town of Mimico as an unemployment relief project.

Construction boom leads to filling of remaining creek valleys. Citizen complaints about flooding and pollution accelerate burial.

Toronto City Council adopts motion to explore feasibility of assessing historical watercourse restoration opportunities.

"Daylighting" is the term given to bringing lost rivers up to the surface where they can help manage stormwater during extreme weather events. Restored rivers provide habitat for plants that capture carbon dioxide while expanding routes for water to find its way to Lake Ontario.

In June 2022, Toronto City Council adopted a motion to explore the feasibility of assessing historical watercourse restoration opportunities across the city—good news for all the lost creeks of Toronto.

"Opportunities to restore or daylight historical watercourses on public parklands or as part of comprehensive redevelopment should be considered where there is an opportunity and it is technically feasible."

This research was compiled by Michael Harrison, who began studying the lost creeks of South Etobicoke in 1996 as President of Citizens Concerned About the Future of the Etobicoke Waterfront (CCFEW). His original report, Toward the Ecological Restoration of South Etobicoke, is available in the circulating collection of the Toronto Public Library.

Harrison contributed a chapter on the lost creeks to HTO: Toronto's Water from Lake Iroquois to Lost Rivers to Low-flow Toilets, published by Coach House Press in 2008. His ongoing research documents both the historical significance and restoration potential of these buried waterways.

Visit the Original Research Blog